Qubits

A bit is the unit of information in the computers we use (mobile phones, laptops, supercomputers etc). A bit can be in two states: \(0\) and \(1\). For convenience, let’s call it the classical bit.

A qubit is the quantum analogue of a classical bit. Qubits are mathematical objects with specific properties. Like spin states, they can be represented as ket vectors. These abstract mathematical objects can also be realised as physical systems that leverage qubits’ unique quantum mechanical properties to build computers that are much more powerful than the best supercomputers that we have today. Therefore, qubits are not just mathematical objects; they can be real, physical systems too.

Just like a classical bit, the qubit also has a state. It can be in state \(|0 \rangle\), in state \(|1 \rangle\), or in a state that is a combination of the states \(|0 \rangle\) and \(|1 \rangle\). Therefore, the most general state of a qubit is:

\[\begin{equation} |\psi \rangle = \alpha\, |0\rangle + \beta\, |1\rangle, \end{equation} \label{eq:super-qubit}\]where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are complex numbers, and |\(0 \rangle\) and |\(1 \rangle\) are called computational basis states.

The values of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are bound by the condition,

\[\begin{equation} |\alpha|^{2} + |\beta|^{2} = 1. \end{equation} \label{eq:normalisation}\]As we see later in the post, Eq.\eqref{eq:normalisation} has physical significance too.

While the states \(|0 \rangle\) and \(|1 \rangle\) can be thought to correspond to classical states \(0\) and \(1\), there is no classical analogue to the state represented by Eq.\eqref{eq:super-qubit}.

Computers routinely determine the state of classical bits. In electronic devices, the two states of the classical bit correspond to two different voltage ranges. In magnetic devices, as in the case of magnetic hard drives, the two states correspond to two different magnetisation of a material.

If we similalry want to find the state of a qubit, then we must find the values of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). Surprisingly, it is practically impossible to find these values, which makes it impossible to find the state of the qubit. We can only get the estimates of \(|\alpha|^{2}\) and \(|\beta|^{2}\) - but not \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) themselves.

What happens when we experimentally examine the state of the quibit? After measurement, the qubit collapses to one of the basis states, and hence, we find the qubit to be either in state \(|0 \rangle\) or in state \(|1 \rangle\). The odds of finding the qubit in state \(|0 \rangle\) is \(|\alpha|^{2}\) and in state \(|1 \rangle\) is \(|\beta|^{2}.\) We will never find the qubit in the state \(|\psi \rangle\).

What does this mean? Does it mean that if we make repeated measurements on the same qubit, we will get state \(|0 \rangle\) with a probability of \(|\alpha|^{2}\) and state \(|1 \rangle\) with a probability of \(|\beta|^{2}\)? No, not at all.

What it means is this: if we have a large ensemble of qubits, all in the same state \(\psi \rangle\), and if we make measurements on each of them, we find some of the qubits in stae \(|0\rangle\) and some others in state \(|1 \rangle\). A statistical analysis of our experiment would show that the odds of finding the qubit in state \(|0 \rangle\) is close to \(|\alpha|^2\) and in state \(|1 \rangle\) is close to \(|\beta|^{2}\).

The probabilities move closer to \(|\alpha|^2\) and \(|\beta|^{2}\) as the number of qubits in the ensemble increases. When we have an infinitely large number of qubits in the ensemble, all in the same state \(|\psi \rangle\), then the probabilities are equal to \(|\alpha|^2\) and \(|\beta|^{2}\). However, the probabilities add up to \(1\), i.e. \(|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^{2} = 1\), irrespective of the number of qubits in the ensemble.

Let’s look at a concrete example now. Consider a qubit in state,

\[\begin{equation} |+ \rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|0 \rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|1 \rangle. \end{equation} \label{eq:plus-state}\]Here, \(\alpha = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\) and \(\beta = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\). When me expermentally measure this state, we find it either in state \(|0 \rangle\) or in state \(|1 \rangle\). The probability of finding the qubit in state \(|0 \rangle\) is,

\[\begin{equation*} |\alpha|^2 = \frac{1}{2} = 0.5. \end{equation*}\]Similalry, the probability of finding it in state \(|1 \rangle\) is \(0.5\).

What does this mean? Suppose we have an ensemble of \(10,000\) qubits, all in state \(|+ \rangle\). When we experimentally determine the states of each of these qubits, roughly \(5000\) of them will be found in state \(|0 \rangle\), while the rest (roughly \(5000\)) will be found in state \(|1 \rangle\). We get this kind of result even though all the qubits were in the same state \(|+ \rangle\) before we made the measurement. The act of measurement simply forced the qubits to collpase to either of the basis states. We don’t know why this happens, but this is how things are.

Bloch Sphere

We can also represent the qubit in state \(|\psi \rangle\) in the form of a complex number:

\[\begin{equation*} |\psi \rangle = e^{i\gamma}\left(\cos\, \frac{\theta}{2} |0 \rangle + e^{i\phi} \sin\, \frac{\theta}{2} |1 \rangle \right), \end{equation*}\]where \(\gamma\), \(\theta\), and \(\phi\) are real numbers. The term \(e^{i\gamma}\) has no observable effects, and can be dropped. Now, the qubit can be written as,

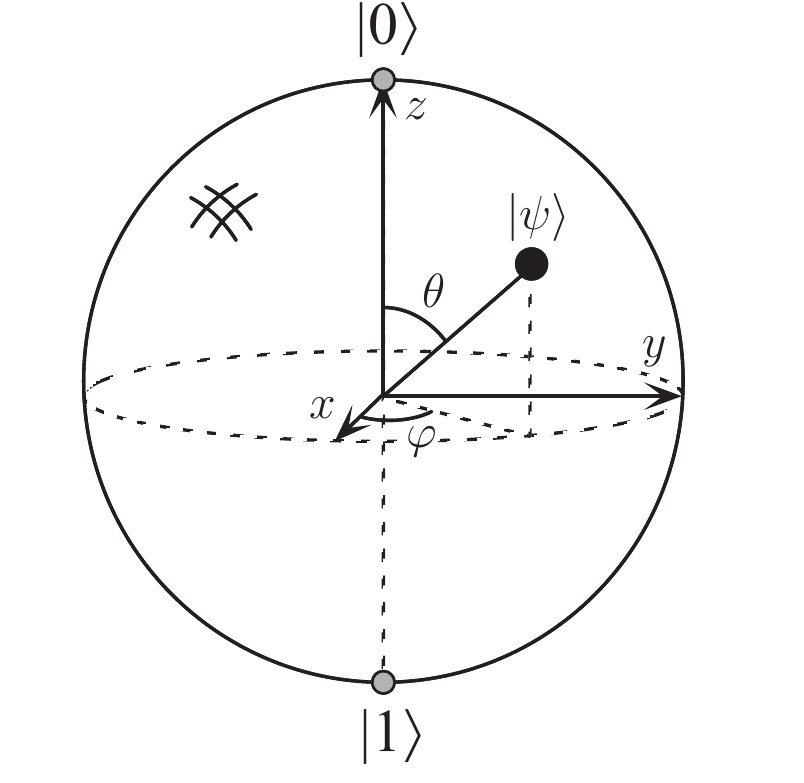

\[\begin{equation} |\psi \rangle = \cos\, \frac{\theta}{2} |0 \rangle + e^{i\phi} \sin\, \frac{\theta}{2} |1 \rangle \end{equation}.\]The numbers \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) define a point on a sphere of unit radius . Such a geometrical representation of a two-level quantum mechanical system is called a Bloch Sphere (see figure below).

Image credit: Nielsen and Chuang. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information

Image credit: Nielsen and Chuang. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information

The computational basis states \(|0 \rangle\) and \(|1 \rangle\) are along the positive and negative \(z-\) axes of a spherical coordinate system with its origin at the centre of the sphere. \(\theta\) is the angle made by \(|\psi \rangle\) with respect to the basis state \(|0 \rangle\). For a fixed value of \(\psi\), \(\theta\) can take any value between \(0^\circ\) and \(180^\circ\). The basis states correspond to \(\theta = 0^\circ\) and \(\theta = 180^\circ\).

References:

- Nielsen and Chuang. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information

- David J Griffiths. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics